|

| Hands-on demo with the Bali govt and NGOs (photo: Lindsay Porter) |

This post is almost a month late, but better late than never. The Bali marine mammal stranding workshop and training was conducted on 1 and 2 May 2013 as a response to the decisions made at national level that several nodal workshops and trainings should be conducted in Indonesia. Four sites are scheduled for 2013: Denpasar (Bali), Kupang (East Nusa Tenggara), Pangandaran (West Java) and Balikpapan (East Kalimantan). We have Bali on 1-2 May. I will travel to Kupang this Sunday for the 4-5 June gig. West Java will be on 3-4 July, and East Kalimantan will be 3-4 September.

The Bali workshop and training was initiated by the Ministry

of Marine Affairs and Fisheries. I was helping the workshop as a consultant to

Conservation International Indonesia. The Ministry invited Dr Lindsay Porter

from the University of St Andrews and Mr Grant Abel from Ocean Park Hong Kong to

assist us with the first responder aspects. The Ministry also invited Nimal

Fernando, DVM from Ocean Park Hong Kong to assist with the veterinary

components of the workshop and training. On top of that, I was assisted by

Sekar Mira from LIPI (the Indonesian Science Institute) and Februanty Purnomo

(Jakarta-based marine mammalogist), both of whom also accompanied me to Subic

Bay (see

this post too). Overall, we had a good, solid team who helped each

other based on our unique capacities we bring onto the table.

We had a range of participants from the local and Jakarta government,

local NGOs (including Bali-based international NGOs), the Navy, coast guards,

and some dive guides from Ena Dive Center. We also had a friend coming from the

Atlas South Sea Pearls in Alor, a very important cetacean hotspot in the

country.

|

| Workshop participants at end of Day One (Dr Toni Ruchimat from MMAF in the middle) |

Now, what exactly did we do in Bali? The first day, 1 May,

was spent briefing the participants of the importance of rapid response during stranding

events, explaining the national initiative of marine mammal stranding network, and

the stranding database from www.whalestrandingindonesia.com.

Grant Abel and Nimal Fernando also presented lessons learned from the Hong Kong

stranding network, including the role of veterinarians in stranding events.

Participants started to understand that the reason we have little understanding

of why marine mammals stranded (and died) in Indonesia was because we never did

any necropsy to stranded marine mammals in the Archipelago (which required,

among others, vets to help us with the analysis). An exception should be made for

East Kalimantan, for my colleague Dr Danielle Kreb has done an excellent job

with mortality analysis there.

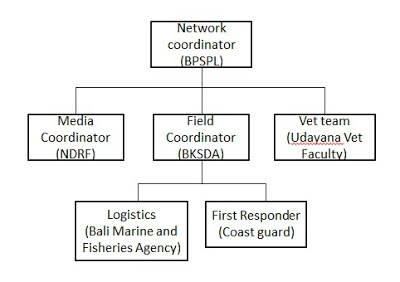

The second half of the day was spent discussing how the Bali

node of stranding network should perform and what the organisational structure

should be. Below is the agreed structure for Bali:

The second day (2 May) brought sunshine to the Sanur Beach

Hotel where we stayed and conducted the event. We spent the morning session

listening to Lindsay taking us through the cetacean species identification, Mira

explaining about cetacean anatomy, and Nimal reiterating the importance of

involving vets in stranding events. Before lunch, Lindsay and Grant gave a series

of video and photographs that showed various stranding rescue scenarios. They also

talked us through the basic scenarios we were going to experience during the

demo session (which was SUPER cool, by the way, the demo!).

Here I once again give the basic ABC of live-stranding

rescue based on several lectures in Bali:

1. Approach the animal from the

side, between the flippers and fluke

2. Protect and clear the blow hole

and eyes from sand and other debris. Do not fill the blow hole with water; it

is not a radiator!

3. Prevent further injuries, by e.g.

digging sand below the flippers and body cavity. Digging sand below the

flippers is to prevent broken flippers. Fill the hole below body cavity with water to help with the re-floating.

4. Support the animal (help re-floating

them if you can), make sure blow hole and dorsal fin are in a straight position

above the water.

5. Cover the animal with wet towel

(or wet shirt) to keep the temperature down. Avoid covering the dorsal fin,

flippers and pectoral fin. Those are their heat loss points. Avoid using

sunblock to the animal (yes to the rescuers, please!) because sunblock is

oil-based and oil will prevent heat evaporation.

6. Use shading (e.g. umbrella) if

possible.

7. Crowd control. Clear the space

between the animals and the crowd; only allow rescuers around the animals.

8. For mass stranding, there is something called ‘Triage’ that I just

learned during the workshop. Wikipedia defines triage as ‘the

process of determining the priority of patients’ treatments based on the

severity of their conditions’. In any mass live-stranding rescues, rescuers

must group the stranded dolphins into three triage categories: most likely to

survive, least likely to survive, and dead. In the ABC of live-stranding

rescue, we have to first save the animals that are most likely to survive. This

rule is contrary to the human triage in ERs where medics have to save those

with the most fatal/emergency cases first, and leave those with minor cases for

later.

After lunch, the team set with nice First

Responder red t-shirts for the hands-on demo. Grant, Lindsay and Nimal had

structured five cool stranding scenarios for us: 1) retrieving the dolphins

from a lagoon to nearby beach; 2) returning the dolphins directly from the beach; 3) returning

stranded dolphins to deeper water with a boat; 4) Mass stranding scenario:

triage, live-stranding rescue, etc; 5) returning the dolphins via a safer beach

front with a land vehicle.

For my team’s

benefit (hey, we are going to do that in a few days in Kupang!), these are the

basic steps for the five scenarios. We will need several sets of basic rescue

kits: stretchers and poles and some ‘dolphins’. Ask some participants to be the

dolphins. Ask two participants per group to be the rescuers; they have to be

good swimmers (you don’t want to end up rescuing the rescuers!).

But beforehand,

here’s Step Zero of the basic technique of putting a dolphin on a stretcher on

land (not from the water, from Geraci & Lounsbury’s Marine Mammals Ashore (1993)). This technique will be particularly useful for

Scenario 4.

Now, returning back to the five

scenarios we gave in Bali:

1) Retrieving the dolphins from a lagoon

to nearby beach

- Setting: hotel swimming pool

- Divide the participants into several groups depending on how many rescue kits we have. In Bali, we eventually had three groups. Delegate a leader within each team.

- Ask the ‘dolphins’ to ‘lie’ still in the middle of the swimming pool.

- Ask two swimmers in each group to swim towards the dolphins and bring the dolphins back (one dolphin per group). The swimmers have to support the dolphin’s belly (which is the dolphin-swimmer’s back, basically) and throat area (the dolphin-swimmer’s neck) as they bring them ashore.

- As the two swimmers return to the shore (pool edge), other members of the team must prepare the stretcher. Stretcher must have the poles inserted already into the sleeves. Ask the team to move the dolphin into the stretcher. What my team did was bringing the stretcher down the water (two more rescuers must get into the water), and then they lifted the dolphin into the stretcher together (easier because the water buoyancy helped). The other team just lowered half of the stretcher from the pool edge and lifted the dolphin into the stretcher.

- When the dolphin is already secured inside the stretcher, the team must lift the stretcher from the water. My team had to lift both sides of the stretcher (the presence of the poles helped) up to the pool edge. The other team just had to lift one side of the stretcher to the pool edge. Either way, the team must do it together to prevent the stretcher becoming unbalanced and further compromised the animal. Delegate someone to make the count when to lift and to put the stretcher down; everything has to be done at the same time.

- Very important: when the stretcher is put down, put it down over a mattress to add support to the dolphin.

|

| Lifting the 'dolphin' from the pool (Photo: Lindsay Porter) |

- After the dolphin is secured inside the stretcher on top of a mattress, the dolphin (inside the stretcher) is carried back to the beach. Again, the team must delegate one person to lead etc. The leader must ensure that all his/her team member knows what he/she is doing. Make sure that there is at least one person whose job is just to take care of the dolphin.

- On the beach, put the dolphin (in the stretcher) on top of the mattress on the ground. Mattress is of particular importance, particularly when the ground is rocky instead of sandy (still, better use mattress on sandy beach as well to reduce respiratory distress to the animal).

- You might not be able to return the animal immediately to the water because you/your team have to assess whether the water is safe for the animal (e.g., no fishing nets lying around etc). If your team doesn’t immediately return the dolphin to the water, put the head against the sea (not head towards the sea) to prevent further stress.

- When it’s time to return the animal to the water, lift the stretcher and turn it such that the animal’s head is facing the ocean. Bring the stretcher into deeper water. Release the animal from the stretcher, but keep supporting the animal (two team members have to handle the stretcher, two more members handling the animal).

- Keep supporting the animal until as far as you can, then give it a gentle push towards the ocean.

- Stay a while to make sure that the dolphin is safe and sound and has returned offshore.

|

| Returning the 'dolphin' to the beach (Photo: Lindsay Porter) |

3) Returning

stranded dolphins to deeper water with a boat

- This situation happens when the team need a boat to return the dolphin to deeper sea. It happened to me once when my friend Kimpul Sudarsono (Reef Check by that time, currently at WWF) and I tried to rescue a young spinner dolphin in Jimbaran Beach, Bali. The tide was flowing, hence the spinner couldn’t return to the sea on its own.

- A simple fisherman boat will do for this case. It’s better if the boat has outriggers like shown in the picture below, for we can tie up the stretchers to the outriggers.

- You will need some guys (or girls) with good rope skills here. I’m definitely not the girl!

- Bring the dolphin inside the stretcher from the back of the boat. In Bali, we had to duck under the rear outrigger-hand to manoeuvre the stretcher such that it was next to the left side of the boat. Tie the stretcher poles to the boat, such to facilitate the easy release of one side of the stretcher that isn’t wedged against the boat. The purpose is to ‘open’ the stretcher from the side and let the dolphin roll into the water on its own.

- Make sure that mattress is positioned between the dolphin and the boat to prevent further injuries to the dolphin.

- Once the stretcher poles are secured on the boat, the boat leaves to deeper water (it actually just stayed there for our practice). As we arrive in deeper water, we release one side of the stretcher and let the dolphin roll into the water on its own.

- If the boat spec isn’t supportive for this scenario, we might have to lift the dolphin onto the boat. Make sure the dolphin stays inside the stretcher, on top of the mattress, to (again) prevent further injuries.

- On every boat scenario, make sure you have someone whose job is solely to look after the dolphin’s welfare (make sure the blow hole and eyes are clear of obstacles, the skin is wet, flippers are secured, etc).

|

| Getting the 'dolphin' on the boat. See the left outrigger? (Photo: Lindsay Porter) |

4) Mass

stranding scenario: triage, live-stranding rescue, etc

- Setting: beach, mass stranding of dolphins.

- This scenario involves the whole participants merged into two groups: the dolphins and the rescuers. Brief the two groups separately.

- The rescuers must decide what to do with this stranding event. The first rule is triage: deciding which animals should be saved first. Again, as in my earlier notes above, rescuers must group the stranded dolphins into three triage categories: most likely to survive, least likely to survive, and dead. In the ABC of mass, live-stranding rescue, we have to first save the animals that are most likely to survive. This rule is contrary to the human triage in ERs where medics have to save those with the most fatal/emergency cases first, and leave those with minor cases for later.

- The dolphins must group themselves into three triage categories: most likely to survive, least likely to survive, and dead. The ‘dolphins’ must decide on what actions (or non-actions) they must perform so that the rescuers can identify their case.

- On cue, rescuers must spread out to identify the stranded dolphins. They must tag each dolphin based on their triage assessment (later, the dolphins can verify whether the tag was correct or not). Rescuers must focus their efforts on cases with the highest chance of survival. Protect the blow hole and eyes, dig sand under flipper and body cavity, cover the body with wet towel and shading, etc etc.

- Then, the rescuers must return the rescuable dolphins back to the sea. Use Step Zero (Geraci & Lounsbury 1993) above to move the dolphins to the stretchers.

- However, the scenario is that the water condition is such that directly returning some dolphins from that beach is impractical or impossible. Rescuers must then relocate the dolphins to a safer beach/bay with a truck.

5) Returning the

dolphins via a safer beach front with a land vehicle

- Continuing from Scenario 4: pick three dolphins to be relocated to another beach with a truck. Again, move the dolphins into the stretcher using the Geraci & Lounsburry 1993 technique.

- Ask the team to lift the dolphins (with the help of stretchers) and bring them to the truck. Bring the mattress along the journey, make sure we have at least one person per dolphin taking care of the dolphin, while another person leading the rescue.

- As the team arrives at the truck, lower the stretchers on top of the mattress. Get two people climbing up the truck. The rest of the team (minus the dolphin care-taker) must lift the stretcher such that (with the help of two people in the truck) the stretcher and dolphin are secure inside the truck, over the mattress.

- When the truck reaches its destination, practice the same care and coordination as the team unload the dolphin (inside the stretcher) off the truck and onto the ground (during the demo, the truck just sits there with engine off).

|

| Getting the 'dolphin' onto a truck (Photo: Grant Abel) |

I hope those notes help those involved in future stranding

events. One last thing I’d like to add is how grateful I am for everyone’s help

during those days. I cannot do it alone without you guys. I cannot describe how

wonderful it was. How energetic it was. How I hope that the beautiful friendships

we have formed from those two days will last for a life time. And I hope that

the national stranding network in this country will move on swimmingly from

this point forward.

1 comment:

As a Marine College professor, I found this post very useful for Marine students, keep posting info like this. Kindly let me know how to subscribe for this blog because i need regular marine updates like this from you. Keep touch with my websites dns maritime institute in chennai | dns maritime institutes in chennai

Post a Comment